Sticky Issues

Panini are known all over the world. It’s the plural of the word panino,

Italian for “small bread roll”. So panini are sandwiches.

But Panini also happens to be the family name of the brothers Giuseppe and

Benito. In 1961, they published their first “Calciatori” album, a collection

of Serie A football stickers. Inter captain Bruno Bolchi was on card number

one, while Milan’s Swedish superstar Nils Liedholm, who had just retired,

was pictured on the album’s cover.

Two years later, in 1963, the two other Panini brothers, Umberto and Franco

Cosimo, joined the company to create a true family business. In the same

year, the “Calciatori” album also included Serie B stickers. Serie C, the

third division, was added in 1967. By the end of the decade, the albums were

an Italian institution.

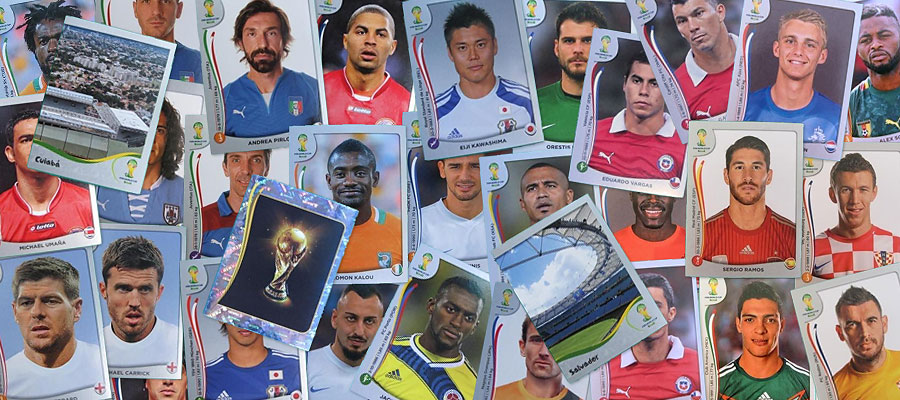

Then, in 1970, Panini published the first of the albums that would soon make

the company a global sensation, the 1970 World Cup sticker collection. This

first album had 271 individual stickers on 52 pages.

There were other World Cup albums available in 1970. One was produced by an

English publishing house called FKS, another was put out in Germany by the

Bergmann company. There was even an album distributed by the US-based

Occidental Petroleum Corporation, although this one didn’t have pictures of

individual players but only team photos of the sixteen sides that competed

in Mexico.

But the Panini stickers were cheaper, more widely available and

self-adhesive (which is common today but wasn’t the norm in the 1960s and

1970s). Gradually, they became the market leaders.

These days, there are many companies which produce football sticker albums,

from Merlin in the UK to the tradition-laden American company Topps. But

Panini’s World Cup album is by far the most popular.

In fact, it’s so popular that a van that was delivering 300,000 stickers to

newsagents in Rio de Janeiro was stolen in mid-April. As the British

newspaper “The Guardian” reported: “It would not be the first time Panini

stickers were stolen. In 2010, before the South Africa World Cup, thieves

broke into a distribution centre in Sao Paulo and made off with 135,000

packets of stickers.”

It’s fun to collect the stickers and swap them with like-minded people,

whether they are kids or adults. However, for a number of decades, before

the advent of the internet and perhaps even since then, some people

cherished Panini’s World Cup albums not for their entertainment value or

their collectability. They wanted the statistics.

In the 1970s, and even in the 1980s, it was very difficult to find stats and

other data from smaller footballing nations. Even very basic information

about the players – such as their birthdates, the caps they had won or the

clubs they played for – could be very hard to come by.

Panini, though, worked hard to fill in the blanks and became very good at

it. The 1974 album had 22 stickers with Italian players, but only six each

from Haiti and Zaire. It was simply very difficult to even find photos of

these players. Eight years later, in 1982, Panini’s album contained at least

eight cards for teams that were making their World Cup debut such as Kuwait,

Cameroon, Algeria and New Zealand. Honduras, another country new to the

World Cup finals, was even represented by an astonishing sixteen stickers.

The Italian company could find the necessary statistics (and the photos)

because it had built a large network of local journalists and Italian

reporters who were familiar with certain regions. However, as Filippo Ricco,

a writer for the “Gazzetta dello Sport” found out the hard way in the

mid-90s, perhaps some of Panini’s statistics have to be taken with a pint of

salt.

As Ricco recalled in his 2008 book “Elephants, Lions and Eagles: A Journey

Through African Football”, Panini asked him for help with their album for

the 1996 Africa Cup of Nations. They needed 316 stickers, Ricco wrote: “The

16 competing teams, the three biggest teams that had failed to qualify, nine

all-time greats and photos of the four cities and four stadiums that were to

host the tournament.”

The journalist did his best to procure all the photos and the personal data

Panini needed to produce this, their first album devoted entirely to African

football.

One of the biggest hurdles for Ricco was finding photos for the players from

Liberia, who had never before qualified for an Africa Cup of Nations.

Finally, and in the nick of time, a Senegalese photographer rounded up the

team, took pictures and sent them to Ricco. There was just one problem. He

only sent the pictures, without the players’ names.

But Ricco was lucky. The best and most famous Liberian footballer of all

time was playing for Milan at the time, George Weah. So Ricco travelled to

Milano, showed Weah the pictures and asked him to put names to the photos.

Of course Weah gladly helped the writer, telling him who was who.

Panini printed the album and a few months later, Ricco found himself in the

same hotel as the Liberia squad. In his book, Ricco wrote: “George says

hello and hurriedly asks what’s happened to the work he did for me. ‘Here it

is,’ I reply and hand him the Panini collection.” The players eagerly

checked out the album – and began to complain. All Ricco heard from everyone

was: “That’s not me!” All the names were wrong.

In his book, Ricco recalls how the whole squad broke into laughter when they

heard that the man who made the mistake was their captain, Weah. Ricco says:

“George defends himself as best he can. One guy’s too young, he says,

another looks like someone else, another still had only played in one

game… and then there was the quality of the photos, very poor, dim light,

bad exposure – you name it.”

The simple truth was probably that Weah just didn’t know the players very

well – after all, he was based in Europe and rarely saw them – but was too

courteous to simply send Ricco away. In any case, this is one Panini album

where some of the stats are definitely wrong. Perhaps it’s not the only one.

© IFFHS 2014